Introduction

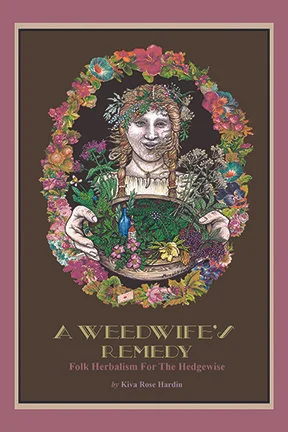

from A Weedwife’s Remedy: Folk Herbalism for the Hedgewise

by Kiva Rosethorn

“Enchantment is about wonder as modernity is about will; and what is needed is not a more efficient or refined will, but will qualified, contextualised and hopefully guided, even restrained, by something else. By the same token, enchantment is unbiddable; it can be invited but definitively not commanded. Hence the ancient understanding of faërie, which precisely coincides with the wild (faërie is nothing if not ecological) as ‘the ancient universe that prevails here on Earth wherever human beings are not in control.”

–Patrick Curry, (Enlightenment to Enchantment)

In the dark of November’s rain, there is a woman sitting atop the fence. In the darkest of the Autumn’s shadows, there is a man standing at the crossroads with a two headed coin in his hand. At the cusp of seasons where Summer dies in Winter’s arms, there is a shape running across the hedge, and she is laughing.

The word hedge has many meanings and implications in English, varying to some degree depending on which side of the Atlantic you reside. Its foundational meaning is as a boundary, most commonly associated with those formed by living plants as is common throughout parts of Europe, especially in Ireland and Britain. From the hedge we have hedge wines, made with foraged fruits of common feral or hedge plants like elderberries, damsons, cherries, blackberries, rosehips, and rowan berries. The hedge schools of Ireland were where my ancestors hid from authorities to be educated in non-conforming faiths under the oppressive rule of eighteenth and nineteenth century English rule. Hedges are where the wild finds refuge, where the feral heart takes root and digs down into ravaged soil to produce sweet bittersweet fruit. To this day, hedges provide much needed diversity through the food and shelter they offer to myriad creatures, especially where there is no native forest left as habitat.

Wooded areas once created a delineation between humans and the wild and even the word forest has its roots in the Latin foris meaning ‘outside’. Eventually, forests in England were primarily intended to hold game for hunters, and as civilizations grew, forests have faded. In more recent times, we have belatedly realized their importance and seek to reintroduce and expand the once ubiquitous woodlands. As the trees come and go, and the flowers push forward and then are pushed back in return, we humans find ourselves, once again, in a place not quite here and not quite there. At this time, in this place, we are stepping from a trouble past into an uncertain future. And there is magic here.

Liminal spaces like this, of both time and place, are of utmost importance in magic, the spaces that are neither here nor there are what allow us to walk between and through the worlds. Humans have always known this, and it is for that reason that magic is known to take place at crossroads, in high places, or at other boundary areas. Where water meets land, where the sky meets the earth, where field meets forest, where human meets other. There’s an Anglo-Saxon phrase, “sittan sundor æt rune” that means to sit apart in secret thought, that references the working of magic.

To sit apart is to imagine the world anew. To ride the hedge is to cross the boundary between this world and the otherworlds. To practice magic is to be removed from accepted reality in a way that allows us to access both new possibilities as well as the inner nature of all things. To understand the past in a symbol, to feel the pull of a certain future in an image, to know that a new love is about to be birthed by the blooming of a flower in your hands. The world is a mirror, the mind is a maze, and the spirit is a wild bird. In all of these things, we may find truth in ways previously unseen and manifest abundance from avenues otherwise invisible.

Black Thorn Key: The Branch That Points The Way

Through the alchemy of time, praxis, and innate understanding the raw branch may assume the form of a wand, key, stave, idol, mask, or olisbos, in accordance with the magical aims of the practitioner. The wood will have thus moved from activity, through contextualized empowerment, to activity anew: the hidden deeds of Art. In this manner the occult herbalist receives the impress of the Tree’s power in omina, having set foot in the Circle of Green. This reflects motions from the potentials of ethos, through the activity of praxis, into the dynamisim of spirit-congress which lies at the heart of occult herbalism.

–Daniel Schulke (Thirteen Pathways of Occult Herbalism)

There is an enchantment in the prick of a bramble thorn. Like so many other forms of magic, it is easy for most to ignore, to tune out, to turn away from in favor of distracting thoughts, anxiety, restlessness. But it’s there, nonetheless. Some would say it’s waiting for us to notice it, but it is we who crave the wound that opens the world. Patterns, enchantments, the endless weave and tangle of energies exist whether we acknowledge them or not. While some magics are made more powerful and obvious by our conscious attention, the slow steep or arrow sharp of what is exists with or without us.

As humans it’s too easy for us to be consumed by the seduction of consensual reality where we, as usual, are primarily responsible for the power and effect of everything. While it is certainly true that are perceptions shape our experience of reality, so much of this is dependent on recognition, not creation. Most of us learn how to make magic happen much more quickly if we can understand that it’s mostly a matter of opening one’s eyes and allowing ourselves to use the connections between us and the world that have always been there.

I have dreamed many times of the black thorn that acts as a key for the door in the tree. Shaped something like the thorn of a Wild Rose and the claw of a feral cat, it is as long as my ring finger and always hangs by a horsehair cord each time I find it. Sometimes I see it glinting against lichen and treebark, other times it’s lodged in slippery rocks in a calm creek, and a few times it was already in the pocket of my skirts or hanging from my neck.

To charm is to draw something or someone to you, whether luck or a lover. To portend is to give a sign, to show the way. To scry is to look in, behind, beyond and see through the veil. There are a thousand ways to access the perception and reality altering ways of what we currently call magic, and there are just as many types of people working the charms that run through our blood and connect us to place, power, and each other.

Magic is a way of being open to a state of enchantment, of being infused with a kind of wonder that opens the eyes to the underlying structure of reality and grants access to the weavings within the world. To be under this enchantment is to move beyond the veil, and magic is what we do there and the ripples those actions have on what we call the real world. This is different than enforcing our will on the world but still allows for subtle shiftings in the patterns that we live and move within. Magic works not because our wills are so strong that we can change reality, but because we have a profound and intimate relationship with an inspirited world, and that relationship allows us to impact our own lives in subtle yet powerful ways.

The fundamental nature of all things at their core is unbiddable, it is wild. Magic, most of all, is wild. We sometimes deceive ourselves into believing that we command the wild at a whim, with a gesture or a prayer or a candle, but this is delusion. We may evoke, invite, or even bargain, but we do not command. Our strength of will is of utmost importance, but in the sense of maintaining radical focus, not in the sense of controlling anything or anyone beyond ourselves. This magic is dirt magic, it belongs to nothing and nobody, and to all of us.

The wise folk of the hedges, we are gathering once again. We know the phase of the moon to gather Mugwort from the stoop, the signs by which to plant the Oats, the song to sing as we charm the Henbane to blossom. Ritual, time, and sight align to point the way inward and onward, and the stars sing in our bones.

The Simples of Peasants: A Book of Weeds & Wild Things For Dark Days

"I know well enough that you have become a curious explorer of the small: weeds and wild things and childish folk. Your time is your own to spend, if you have nothing worthier to do; and your friends you may make as you please. But to me the days are too dark for wanderers' tales, and I have no time for the simples of peasants.”

- Saruman to Gandalf, The Lord of the Rings, by J. R. R. Tolkien

Gentle Reader, you hold in your hands a humble volume about plants common yet often unknown, wisdom that has been handed down across countless generations, but is always halfway hidden in shadow, about a world that is only steps from most of our front doors and yet rests in the liminal spaces so easy to miss. Weeds, wayside plants, and old wives figure largely here, for we are greatly in need of their wisdom. There is much to be learned from wanderers’ tales in a time where we increasingly lock ourselves away in isolated towers and neglect the knowledge of ancestor, land, and spirit. But some weedwives still gather Nettle by the dooryard and sow Nightshade in the back garden. By the turning of the moon, they harvest and plant, garble and weave, tincture and infuse.

This book is a love letter to the Hedgewise, those folk who hold simple dirt and deep roots in one hand and the mysteries of the dreaming in the other. I wrote these words for all you witches at the edge of the wood, you hedge riders and hooded wanderers, for those serving their community through hard work and hunches that won’t be ignored. And most of all, for you who will always be unbiddable, who remain in wide-eyed wondrous love with the weeds and always seeking to pass your healing secrets to the next needing hand. Rogue healers with feral hearts that seek and serve regardless of legality, popularity, or even safety. We do this work and dream these dreams because we are called to it, and because it must be done.

A Weedwife’s Remedy is the first in a series of books meant to serve as guides and touchstones for those who consider themselves students of healing and devotees to the magic of the plants. I offer here clinical experience, personal insights, folklore, and an abiding passion for the plants that have shaped my life in this world, and opened a portal into a new one. For almost two decades I have stood witness as the herbs healed wounds, soothed spirits, and nourished at a bone deep level…. but most of all, I have watched them transform myself and the people I work with. This transformation, so simple and so necessary, is exactly what we need in these troubled times.

The simples of peasants will long continue to illuminate the dark and ease the birthing pains of new worlds, so I invite you, come stand by me.

“If you are a savage, stand up.

If you are a witch, a dark queen, a black knight…

If you swear by the moon and you fight the hard fight,

Come stand by me….

For we all have stripes, and we all have horns,

We all have scales, tails, manes, claws and thorns

And here in the dark is where new worlds are born.

Come stand by me.”

-Cat Valente, from A Monstrous Manifesto

Roots in The Night Sky: Folk Practices & The Nature of Transformation

I believe that magic is something humans do and probably always have done. In the recent past, at least in the West, we have largely moved magic and sorcery into a subset of religion, orthodox or heretical, depending on the context of those involved. My personal belief is that this is an inversion. I believe that religion is an offshoot of sorcery and that sorcery (and the animism that underlies it) is the probable root of all human culture.

–Aidan Wachter (Six Ways: Approaches & Entries for Practical Magic)

Folk magic is a continuation of rituals, practices, beliefs, and perspectives from the people, all the people. Which includes any and all of our ancestors who at any time practiced any form of magic, whether faith based, ritualistic, or made up only of need, kitchen herbs, and scarlet thread. As with most things passed down through generations of humans from all over the globe many of these practices can be considered syncretic to some degree, but there are also infinite variations and expressions throughout time and cultures.

Consistent with anything folk, this sort of magic is subject to change, particularly practical adaptation to the needs of the present. Folk magic is known for taking from many sources, whether formal religion or ceremonial magic or exposure to another community or individual’s ways of doing things. The point is specifically what will work for the person at the present time. While practitioners may use a wide array of tools, words, ways, it is always transformation and insight that lies at the root of what we are doing. The words and the way change, but our bond to spirit remains the same.

What matters is that the practice upholds and honors the practitioners relationship with place, spirits, and that it is as elegant and specific as possible. And most importantly, that it works! We can make the working of change and transformation as complicated or as simple as we like, history and ancestral traditions will uphold either end of the balance as long as we can sustain the focus, will, and need required to fuel the fire.

Some people hold to the view that magic is purely a psychological phenomenon and that it is primarily a matter of the way in which we see the world and how we interpret the images, dreams, symbols, and other phenomena the unconscious holds forth to us. I see the unconscious – whether personal, phenomenological, or collective– as profoundly powerful and certainly capable of changing a person’s, or many persons’, lives. I also see that unless our definition of the collective unconscious extends to the more than human world, it cannot encompass the full extent of what magic is and does.

It is easy to say that everything is connected. It is less easy to act as if those words are ineffably, irrevocably, and infinitely true.

At the root of all is this, is the needful truth that magic acknowledges all things are alive. Some degree of animism seems innate to the very practice of most forms of magic, including folk traditions and practices. The understanding that the whole world is inspirited and that an animating spirit is not limited to humans, or even animals, is in some ways both radical and common sense. I know of no tribal culture from any area of the world who were not animistic in outlook.

We do not need history to show us the obvious, simple observations of the world teaches us that sentience stretches between our fingers and the root tips of every tree. Folklore and tradition passes on tellings of women clothed in moss deep in a forest far from here and talking trees just around the bend not to give us anthropocentric compassion, but to remind us of where we come from and how the Other still speaks to us.

The liminal is here, transformation awaits, and the key is already in our hand. We are the Hedgewise, the folk that gather among the thorns. We sit apart from the village in secret thought, passing the black thorn key from hand to hand.